Unlike the similarly named Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) seldom receives research interest except in studies examining several of the 10 personality disorders or else specifically Cluster C personality disorders (which also include avoidant and dependent personality disorders) as identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5. OCPD serves as the sole focus of investigation far less often. The objective of this paper is to distinguish OCPD from other similardisorders; review the existing literature on OCPD; and propose that social anxiety, which is based on performance dynamics, is often a ramification of OCPD. This paper draws on a review of more than 20 peer-reviewed academic journal articles as well as more than 35 years of clinical observation and treatment of thousands of subjects diagnosed with social anxiety. The author proposes that OCPD is often an underlying cause of social anxiety and discusses the value of further research to prove this link exists and determine how best to synthesize OCPD and social anxiety treatment modalities.

For more than three decades, the author's psychotherapy practice has specialized in social anxiety, the primary subgroups being public speaking anxiety; the fear of being noticeably nervous because of dysfluency, erythrophobia, and hyperhidrosis; selective mutism; and pervasive social avoidance. Social anxiety is driven by performance dynamics. That is what separates it from other anxiety disorders. The author's clinical experience has demonstrated that understanding the perfectionist dynamic of OCPD can enhance the efficacy of treatment for social anxiety. The sample size for the clinical observations reported here comprises thousands of subjects who sought help from the author's practice with self-diagnosed anxiety disorders, primarily social anxiety. The author and his team later diagnosed them with social anxiety, performance anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder-or a combination thereof. The treatment was provided by the author or by one of the licensed associates he supervised.

The following case examples elucidate the ways in which the perfectionistic dynamic drives social anxiety:

Case 1

Brittany, a second-year law student, extensively analyzed potential questions for her course in labor law. The professor cold-called students every day; in fact, cold calling was 50 percent of the grade for that course. Brittany knew she could be called on at any time. She was determined that her answers be accurate and sound "just right." Fearful and exhausted, she invariably shut down when called on. Her summer internship and later job interviews took on the same quality. She was so afraid she wouldn't sound "just right" that she overprepared to the point of exhaustion, made a poor impression as a result, and received no internship or job offers.

Case 2

Kate, 46, was a leading sales associate with a three state territory known for her dedication and personal service. She was determined to meet face to face with any client for any order, no matter how small. While this determination led to career success, the excessive and obsessive emotion that drove that determination also drove her panic in group presentations. That panic was her reason for seeking treatment.

Case 3

Jason, 36, never experienced intimacy with a woman, though he longed for companionship. His mindset was that when he had sex for the first time, his performance had to be "just right" or perfect. This self-imposed pressure and impossible expectation, which the author refers to as "James Bond Syndrome," caused Jason's performance anxiety and intimacy phobia.

Case 4

Dan, 52, a successful salesman, experienced panic attacks in group presentations. These experiences led him to avoid presenting before others, which put his career at risk. His compulsion to project a perfect image, because anything less put his "personhood" on the line, created his panic.

OCD versus OCPD versus Social Anxiety

Both lay people and professionals sometimes mistake Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder for the similarly named Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, which is characterized by uselessly repetitive actions such as checking or washing. An often visible, usually time-consuming disorder, OCD affects about 2.3 million people, the National Institute of Mental Health reports. OCPD, on the other hand, can be invisible from the outside. Like other personality disorders, OCPD is not uncommon. In fact, a landmark study of 43,000 test subjects concluded that in 2001-02, 7.9 percent of Americans-some 16.4 million-had OCPD.

Social anxiety is rarely linked to Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder, based on my review of the literature. Because OCPD is unknown in the lay population, it is almost certain that very few nonprofessionals have considered the connection. Social anxiety is present in an estimated 6.8 percent of the U.S. population, according to the National Institute for Mental Health.

A comparison of the three diagnoses reveals similarities and differences (Table 1). As mentioned earlier, OCD is clearly differentiated from the other two disorders, showing similarity only in the individual's preoccupation with a particular fear; the compulsion or action taken differs considerably. The two most similar conditions, OCPD and social anxiety, share more characteristics. OCPD and social anxiety have in common the pervasiveness of anxiety and the preoccupation with being perfect. Both disorders are characterized by an expectation of being "negatively evaluated." Both result in a highly controlled behavior-relentlessness and rigidity of OCPD is akin to social situations being "avoided or endured with intense fear or anxiety." In both conditions, the fear and worry are disproportionate to the consequences that could arise from failure.

Table 1. Criteria for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder, and Social Anxiety Disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Specify if: Specify if:

|

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality DisorderA pervasive pattern of preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by four (or more) of the following:

|

Social Anxiety Disorder

Specify if: |

Source: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Obsessions are, to some degree, present in all three. OCD's anxiety-caused obsessions are alleviated temporarily by enacting compulsions (as with a woman whose extreme fear of losing money led her to count her money several times an hour or someone with an overwhelming fear of injury being mitigated by intense and seemingly nonstop cleaning . OCPD's obsessions persist unabated, compelling actions that become futile (as with working on a report past the deadline because it's "not quite right" and then ultimately failing because the assignment is past due). In social anxiety, obsessions lead to an action that is, paradoxically, a lack of action: avoidance of the stressor.

What Are Obsessions and Compulsions?

Obsessions are repetitive thoughts and preoccupations about situations or events that create anxiety or feel extremely difficult to control. Obsessions focus on particular things: a fear of germs, of being hurt or hurting someone, or religious or sexual thoughts, to cite some common examples. Compulsions are attempts to alleviate that anxiety with action-whether that means excessive cleaning or organizing, washing the hands five times before cooking dinner, checking the door numerous times after locking it, or starting an assignment over from the beginning if there is a mistake. The compulsive behaviors that subjectively alleviate anxiety in the moment are in reality a futile attempt for anxiety control that takes the sufferer deeper into the disorder. But the toll they take is significant. Sufferers may spend more than an hour a day acting out their compulsions and sometimes end up being late to work or social events, or not showing up at all (National Institutes of Mental Health).

Clinical efficacy requires distinguishing the two as follows: OCD's individual compulsions lead to actions that are completed and, at least for a time, alleviate the obsession that prompts them; whereas the obsessions of OCPD are rarely alleviated by the behavior they cause. In other words, there's very little potential for fulfillment as perfection is an unattainable phenomenon. OCPD is not limited to certain types of actions, but rather is a constant obsessive drive for perfectionism. The excessive and often impossible demands of the internal critical script are compensation for a deeper emotional insecurity. No matter how hard one tries, "good enough" is never good enough.

A person with OCPD seems to pursue perfection for its own sake. The author has witnessed a clear clinical pattern: The ongoing and relentless self-imposed pressure for perfection can create a direct link to panic disorder. The constant excessive pressure from one's internal critical script, which peaks in challenging performance scenarios, exacerbates adrenaline flow, which causes panic. Once a panic episode occurs, the person obsesses about the symptoms that resulted, usually the fear of being noticeably nervous. This obsession can lead to a compulsion to avoid the stressors that caused those symptoms as the emotions of embarrassment, shame, and humiliation rule.

There is not as much research or clinical data on OCPD as on OCD (de Reus et al., 2012), nor is OCPD a part of the vernacular, as OCD has become thanks in part to the media's human interest stories about the significant daily challenges of OCD. For example, consider the portrayal of the obsessive germophobic detective "Monk" in the eponymous television show that ran 2002-2009 on the USA network and was watched by millions. These days, a person might say, "I'm so OCD" to refer to a general sense of orderliness, hypervigilance, or perfectionism. In fact, however, that type of hyper-perfectionism is actually the hallmark not of OCD but of OCPD, which is characterized by a rigid preoccupation with orderliness, perfection, and rules. The perfectionism turns toxic as increasingly impossible standards are created.

What's Wrong with Perfectionism?

Productivity, conscientiousness, responsibility, and accountability are considered good qualities in western culture; therefore, it can be easy for the pathology of the OCPD sufferer to remain hidden. But too often, the individual is waylaid by the pervasive feeling of "not quite right" that has OCPD sufferers return to a project again and again, even when that project is past due; or they might micromanage even the simplest tasks. In fact, research shows that OCPD can lead to success when perfectionism is an asset, especially in the workplace (Skodol, Oldham, et al. 2005). That benefit may not last throughout a career, however:

Based on our own clinical experience…[the] beneficial effects [of OCPD] may occur until the age of around 50. At this stage, a number of individuals with OC personality pathology often are no longer able to meet their own highly perfectionistic standards, eventually resulting in severe psychological complaints such as occupational difficulties, burnout, depression and marital problems….Put differently, it is our impression that OCPD patients do not age well…. Presumably, many persons with OCPD function adequately for quite some time but may eventually feel distressed and depressed if they realize that they are not as successful in their work and social relationships as others. If this would be the case than distress and depression should develop as a result of problems related to the OC personality pathology rather than the other way around. (de Reus, 2012) .

If depression develops as a result of OCPD "rather than the other way around," to use de Reus's phrase above, then it follows that anxiety-and specifically social and performance anxiety-could arise from a bedrock of OCPD as well. This connection appears to have gone unnoticed in the world of academic research on mental health and personality disorders in particular. But the author's observations over three-plus decades of clinical experience appear to confirm the extent to which the perfectionist component of OCPD is the foundation on which social anxiety is built.

The author's clinical architecture is based on the premise that while being in pursuit of peak performance is laudable; it is absurd to be paralyzed by the fear of not being perfect. To align with this belief, the patient needs insight into the development of the excessive internal critical script and the anger and rage it creates at an unconscious level.

Differentiating Social and Performance Anxiety

Social anxiety has replaced social phobia as the term to describe an excessive fear of at least one social situation in which the person faces possible scrutiny from others. Table 1 delineates the diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 distinguishes the performance dynamic present in some expressions of social anxiety as follows:

Individuals with the performance only type of social anxiety disorder have performance fears that are typically most impairing in their professional lives (e.g., musicians, dancers, performers, athletes) or in roles that require regular public speaking. Performance fears may also manifest in work, school, or academic settings in which regular public presentations are required. Individuals with performance only social anxiety disorder do not fear or avoid nonperformance social situations.

It is from this definition that the term "performance anxiety" derives. Whereas social anxiety may refer to social situations in general, what people generally refer to as performance anxiety typically refers to a specific activity (such as playing a sport or performing music) (D. H. Powell, 2004).

It follows that another quality that differentiates debilitating performance anxiety from other forms of social phobia is that the individuals who experience it are less concerned with the scrutiny of others than their own judgment of how well they will carry out the feared task. Unlike other social phobics, whose primary fear is how others will judge them, these individuals are less bothered by the scrutiny of others than by the morbid fear of being unable to execute a task in a way that is acceptable to them. Later, they may exhibit considerable post-event rumination (Abbott and Rapee, 2004), believe that they performed poorly, and worry about the impact of their failure on others, but not while they are performing. (Powell, 2004).

An example of performance anxiety in action would be Wade, a 17-year-old straight-A student who quit the lacrosse team after a move that he thought had cost his team a regional win. No one said they blamed him, but his self-blame was in overdrive. He chose to switch to cross country because the solitary sport allowed him to avoid the anxiety of working with and potentially disappointing teammates. An example of obsessive compulsive personality disorder would be Victoria, a piano prodigy who lost out on scholarship to Juilliard after staying up all night to rehearse to be sure she was "perfect" and then, exhausted, giving a poor performance at a regional competition; in this case of OCPD, it is the pursuit of perfection that, paradoxically, resulted in imperfection.

OCPD's Toxic Perfectionism

OCPD is "toxic perfectionism." It is overcompensation designed to stave off intense feelings of embarrassment, humiliation, and shame. Fears of experiencing these emotions drive the perfectionism which, in turn, drives the anxiety. "If I am perfect, no one will know I am nervous." "If I am not perfect, I will be humiliated by the focused attention on me." OCPD sufferers hold onto their disorder more tightly because, they argue, "It works!" (Cullen, 2008). That said, Chessick (2001) reported people with OCPD were actually aware of their suffering and wanted relief. Many of the author's patients with performance anxiety have credited their career success to perfectionism. They didn't seek help with changing their perfectionism. The reason they sought treatment was to put a stop to the panic it created, primarily related to the fear of being noticeably nervous.

Understanding Perfectionism from a Mind State Perspective

The following model, based on the psychology of transactional analysis, developed by Eric Berne and others, can facilitate a clinical and functional understanding of perfectionism. In transactional analysis, there are five mind states.

- Nurturing parent (NP): promotes growth, teaches, acknowledges, and provides support. "Take the risk." "You're doing your best." "It's okay to make mistakes." "Good try." "You did well."

- Critical parent (CP): expresses authority, evaluation, judgment. "You're doing it right." "You're doing it wrong." "That was not your best work." "That was good work." "You need to worry to be in control."

- Adult (A): Internal computer. Not contaminated by emotion. Displays logic and objectivity. "The meeting is at 8 a.m." "The team that scores the most points will win." "In order to solve the problem, I have to integrate information."

- Adapted Child (AC): Learned behavior and emotion; conforming, cooperating, compromising, and manipulating. "I have to do this right." "I have to be perfect." "I feel confident." "I need to avoid due to anxiety."

- Natural Child (NC): The truth of desire, exploration, creativity, the development of ideas, genuine emotion, expresses spontaneity, exploration, joy. "Just do it!" "Do what you want!" (Berent and Lemley, 2010).

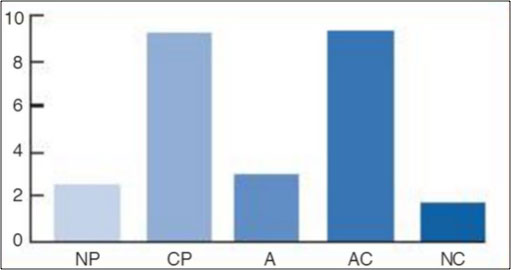

Figure 1 demonstrates perfectionism homeostasis. This system is dynamic - all five states are in play all the time. All are important. There is no such thing as a bad state. The clinical issue is synergy. The primary dynamic is the interaction between the critical parent and the adapted child.

Figure 1. Mind states and perfectionism.

Source: Adapted from Egograms, John M. Dusay, M.D. Harper and Row, 1977.

The critical parent is the driving force of perfectionistic pathology, with its messages of "If you are not perfect people will see who you really are," "You are not worthy enough," "You will embarrass yourself," and "Don't be yourself." These messages activate the excessive activity of the adapted child in the form of panic (especially for individuals suffering from autonomic hypersensitivity.

The critical parent - adapted child reflex becomes ingrained when perfectionism is at play. It can be considered a psycho-physiological tic. This tic creates a vicious cycle in which the OCPD sufferer persists at a task long after his or her efforts have stopped being effective. He or she just cannot leave it alone. Everything feels incomplete or "not just right."

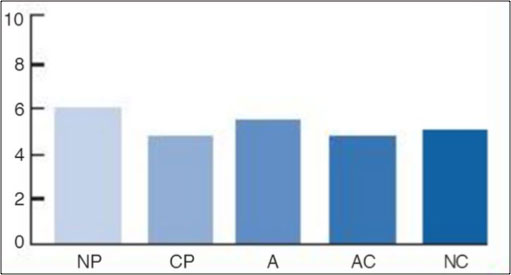

The following mind state graph depicts the resolution of the toxic perfectionism that characterizes OCPD. Clinical strategies aim at increasing the nurturing parent, adult, and natural child. As this occurs, the critical parent - adapted child reflex lessens. Resolution requires a dialing down of the excessive internal critical script, which allows the other mind states to adjust accordingly.

Figure 2. Mind states and perfectionism resolved

Source: Adapted from Dusay (1977).

Conclusion

In his decades of clinical practice, the author has treated or supervised the treatment of thousands of patients struggling with social and performance anxiety. Often an obsessive-compulsive personality was the bedrock on which the anxiety disorder was built. Given the degree to which performance anxiety seems to be an expression of an underlying obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, numerous areas for further study present themselves.

Because of the dearth of literature about performance anxiety in areas other than sports and music, it could be worth researching anxiety in other performance areas besides athletics and the performing arts, especially in venues that require speaking in public.

Further inquiry into the relationship between OCPD and social anxiety is needed to determine whether the author's success can be documented and replicated by other practitioners in the mental health community. This could build on or incorporate the work of Albert et al. (2004), Diaferia et al., 1997; Grant et al., 2005; and McGlashan et al., 2000).

Continued inquiry is especially important given that social anxiety remains, in this author's clinical experience, the quintessential disease of resistance, and studies regarding clinical efficacy are limited.

- Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2012). Phobic and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Springer Science + Business Media.

- National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2004), Landmark survey reports on the prevalence of personality disorders in the United States, press release, August 2.

- National Institutes of Health.

- National Institutes of Health. The NESARC also found that "9.2 million (4.4 percent) had paranoid personality disorder; 7.6 million (3.6 percent) had antisocial personality disorder; 6.5 million (3.1 percent) had schizoid personality disorder; 4.9 million (2.4 percent) had avoidant personality disorder; 3.8 million (1.8 percent) had histrionic personality disorder; and 1.0 million (0.5 percent) had dependent personality disorder."

- National Institute of Mental Health. Social Phobia. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/social-phobia-among-adults.shtml.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). (2013). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, pp. 237-238.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), pp. 678-679.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), pp. 202-203.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.).

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.).

- National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-among-adults.shtml.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.).

- National Institute of Mental Health, When unwanted thoughts take over: Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/when-unwanted-thoughts-take-over-obsessive-compulsive-disorder/index.shtml.

- Kung, M. (2009). "Monk" breaks basic cable ratings record. December 7. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2009/12/07/monk-finale-breaks-basic-cable-ratings-record/.

- Ullrich, A., Farrington, D. P., and Coid, J. W. (2007). Dimensions of DSM-IV personality disorders and life-success. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21, 657-663.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.), p. 203.

- Ibid.

- Powell, D. H. (2004). Treating individuals with debilitating performance anxiety: An introduction, 60, 801-808.

- Abbott, M. J., and Rapee, R. M. (2004). Post-event rumination and negative self-appraisal in social phobia before and after treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 136–144.

- Cullen, G., Samuels, J. F., Pinto, A., Fyer, A. J., McCracken, J. T., Rauch, S. L., Murphy, D. L., Greenberg, B. D., Knowles, J. A., Piacentini, J., Bienvenu, O. J., Grados, M. A., Riddle, M. A., Rasmussen, S. A., Pauls, D. L., Willour, V. L., Shugart, Y. Y., Liang, K. Y., Hoehn-Saric, R., & Nestadt, G. (2008). Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with treatment status in family members with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 218-224.

- Chessick, R. (2001). Acronyms do not make a disease. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 21, 183-208.

- Berne, E. Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships. New York: Grove Press, 1964.

- Berent, J., and Lemley, A. (2010). Work Makes Me Nervous: Overcome Anxiety and Build the Confidence to Succeed. New York: Wiley and Sons.

- John M. Dusay, MD. Egograms. New York: Harper and Row, 1977.

- Albert, U., Maina, G., Gorner, F., and Bogetto, F. (2004). DSM-IV obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: Prevalence in patients with anxiety disorders and in healthy comparison subjects. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 45, 325-332.

- Diaferia G., Bianchi, I., Bianchi, M. L., Cavedini, P., Erzegovesi, S,, and Bellodi, L. (1997). Relationship between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry.38:38-42.

- Grant, B. F., Hasin, D. S., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Chou, S. P., Ruan, W. J., and Huang, B. (2005). Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 39, 1–9.

- McGlashan, T. H., Grilo, C. M., Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Shea, M. T., Morey, L. C., et al. (2000). The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Baseline axisI/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 256-264.

|

About JonathanJonathan has pioneered psychotherapy for social anxiety, public speaking anxiety, and performance anxiety since 1978. He has worked with thousands of individuals of all ages in individual, family, and group therapy. He is the author of "Beyond Shyness: How to Conquer Social Anxieties" (Simon & Schuster) and "Work Makes Me Nervous: Overcome Anxiety and Build the Confidence to Succeed" (John Wiley &Sons, Inc.) Jonathan is an expert in media performance having been featured extensively on television, radio, and in print. This experience includes Oprah, NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN, FOX, The New York Times, Newsday, The Chicago Tribune, and The Boston Globe. Listen to him on WFAN SPORTS RADIO. Jonathan has extensively researched and developed clinical programs for the avoidant and dependent personality. He is a "diplomate" in clinical social work and is certified in New York State. In addition, he is certified by The Association of Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. To view Jonathan Berent's pioneering work with Social Phobia, view the 1988 Sally Jessy Raphael Show by clicking here.To view jonathan talking about Workplace Anxiety on Long Island News Jobline, click here. |